The Great Immoderation

Re-shoring manufacturing could increase the volatility of US GDP growth and benefit value investing strategies

Investing strategies of the last two decades have generally calibrated to a specific cocktail of economic conditions: limited adverse shocks, low and declining interest rates, and modest but consistently positive output growth. Here I consider the investing implications of a counterfactual where our economic world becomes more volatile. Specifically, I look back in time and across countries to assess how a specific investment style – value investing – has fared when output growth becomes less certain. Empirical data supports the idea that value strategies are fueled by economic volatility. The heightened cash-flow sensitivity of these cheap and cyclical firms makes them relatively riskier during tumultuous periods, increasing their expected returns.

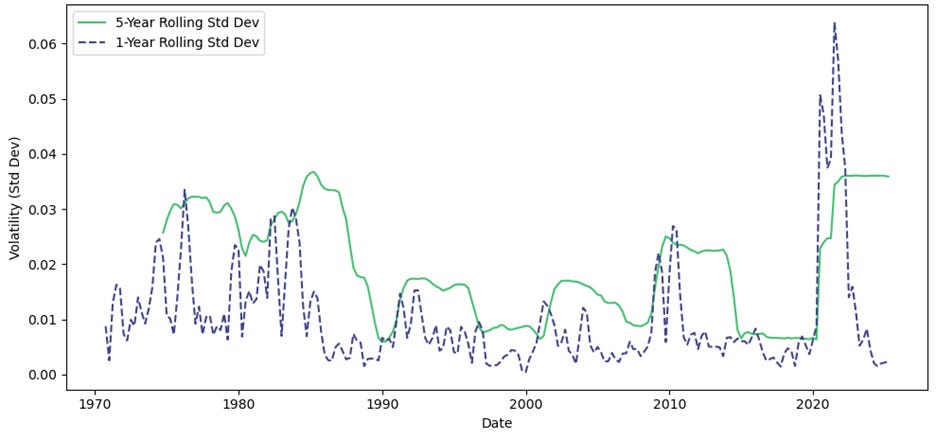

Blanchard and Simon (2001) were first to document the fact that the US economy has slowly become more stable over a period of many decades, noting: “the decline [in volatility] is not a recent development, but rather a steady one, visible already in the 1950s and 1960s.” The authors’ core observation is that the volatility of output growth, measured by its standard deviation, declined by a factor of 3 between 1950 and 2000. In other words, the trajectory of GDP growth became less bumpy. Figure 1 shows output volatility in the US from 1970 until today. During the 70’s and 80’s, 5-year GDP volatility ranged between 2.0% and 3.0%. From the 90’s through 2020, GDP volatility was structurally lower, with 5-year values banded between 0.5% and 2.5%. COVID created a dramatic spike in the data, which sent GDP volatility back to levels not seen for 40 years.

Figure 1: 1-Year and 5-Year Rolling US GDP Volatility, 1970 – Present

Source: S&P Capital IQ, Countervail Analysis

Economists debate the causes of this decline, which Ben Bernanke termed the ‘Great Moderation’. Some argue the phenomenon is driven by structural changes in the economy and improvements in inventory management, others point to changes in monetary policies, and still others say it was simply the absence of adverse shocks like famine and war – ‘good luck’. While each of these ideas has merit, the argument that our economy has become structurally more stable makes intuitive sense. Anecdotally, as we transitioned our labor force from agriculture, to manufacturing, to services, the spillover effects of slowdowns would have become less severe. We effectively graduated from firing people, to firing machines, and now to firing software. The second order economic impacts diminish with each step of this transition.

As investors walk through the various potential impacts of the proposed tariffs, it seems likely that we’re heading into a more economically volatile period. For instance, warehousing and logistics behemoth Prologis just reported earnings, and cited a short term increase in demand for warehouse space as companies have boosted inventories to manage tariff uncertainty. In another sign of volatility, air traffic data shows steep declines in inbound travel to the United States. In the medium term, while the GDP pie will keep growing, its constituent components – specifically the balance of consumption and investment – are likely to change and induce more volatility still.

Here I consider how changes in GDP volatility could impact returns to value investing strategies. To investigate this question, I created a data set comprising 20 countries, their historical output volatilities, and their respective country-level value factor returns. Figure 2 shows the 12-month forward returns to the value factor per level of output volatility in Canada, the UK, Japan, and Italy. The high-level results indicate that economic fluctuations likely drive different return patterns for value investors. The 12-month forward returns to the value factor are generally increasing in volatility levels. Across the full sample period, changes in output volatility among these 20 countries bear an average 41.3% cross-correlation. So while high-volatility observations are sparse, the circumstances of individual countries provide enough variation to study the link between output volatility and value investing.

Figure 2: 12-Month Forward Value Factor Returns by Country and Level of Output Volatility, 1970 (or Earliest Available) - Present

Source: S&P Capital IQ, Ken French Data Library, Countervail Analysis

For most, the term ‘value investor’ likely conjures an image of Warren Buffett reading company annual reports and appraising the difference between a company’s fundamentals and its price. In the world of quant investing, value means something different. In its simplest form, quant value investors simply buy the cheapest stocks in the market regardless of the fundamental picture. Long term historical studies using vast amounts of data across countries provide robust evidence that following a simple strategy that blindly invests in cheap companies works well.

There is some disagreement about why quant value investing works: some say it’s more risky while others say it harvests alpha in mispriced securities. There is no strong consensus, and there’s likely truth to both sides of the argument, but I personally find Campbell and Vuolteenaho's (2003) argument that value stocks are more sensitive to aggregate cash-flow news particularly compelling. In essence, value stocks tend to be more cyclical and more exposed to the fluctuations of the broader economy than other types of stocks and other types of quant investing strategies.

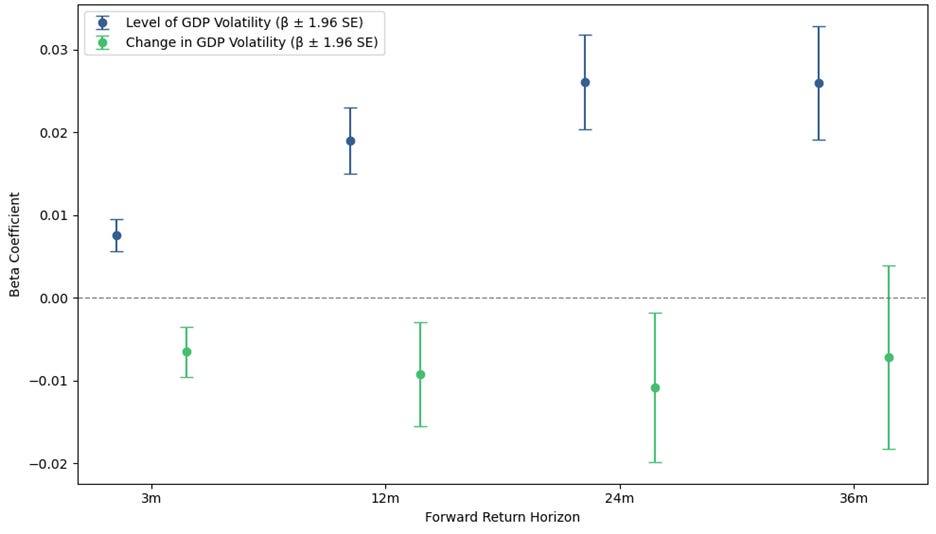

To the extent that the value investing is ‘risky’, and its returns are more sensitive to changes in economic states of the world, I think it is reasonable that both the level and change in output volatility would influence the future cash flows attributable to these firms and explain some of the performance to value strategies over time. Figure 3 analytically confirms this intuition. The data show the results of a series of regressions that attempt to identify how the level and change in output volatility impact returns to the value factor at horizons spanning from 3 months to 3 years. Across all horizons, high levels of output volatility are positively associated with high future returns to the value factor. In the short term, increases in output volatility are negatively associated with returns to the value factor, but this effect becomes less meaningful over time.

Figure 3: Explanatory Power of Output Volatility For Value Factor Returns across Time

Source: S&P Capital IQ, Fama French Data Library, Countervail Analysis

Endnotes: [1], [2], [3]

These results make sense. When the economy hits a speed bump, these economically sensitive firms – cheap, cyclical businesses – are impacted significantly in the short term, creating near term drawdowns but increasing their expected returns. In the long term this impact becomes negligible, and conversely, when economic conditions later stabilize from a point of great uncertainty, value firms tend to do exceptionally well. To reinforce these observations, I create a strategy that allocates capital to the value factor in different countries depending on their level of output volatility. Figure 4 shows the results to portfolios of ‘High, ‘Medium’ , and ‘Low’ volatility countries. The data show that value investing in ‘High’ volatility countries has achieved roughly ~4.0x the returns of value investing in ‘Low’ volatility countries since 1970.

Figure 4: Returns to Value Investing across Countries based on Output Volatility

Source: S&P Capital IQ, Fama French Data Library, Countervail Analysis

Endnotes: [4], [5], [6]

This meta strategy underscores that output volatility and economic uncertainty appear to fuel value investing strategies. Today investor portfolios have grown fat on market-weighted indices that are heavily tilted toward a breed of company that has thrived in a low volatility environment. While this has worked phenomenally, tariffs appear likely to change economic conditions. Attempts to increase our manufacturing base will very likely make output growth more volatile. And while the data indicate that economic uncertainty will create near-term pain for value investors, it will likely improve long-term prospects for the strategy.

Technical Appendix and Methodological Notes: